Remembering John Dalton

Chair of the RSC Historical Group, John Hudson, with Steve Howe impersonating John Dalton Picture: © David Leitch

John Hudson, Chair of the RSC Historical Group, tells us about the life and work of John Dalton, and reports on his 250th anniversary celebrations held in Manchester earlier this year.

2016 marked the 250th anniversary of John Dalton’s birth. He was born into a Quaker family, probably on 6 September 1766, but curiously his name was not entered in the Quaker register. For various reasons it was not possible to celebrate the anniversary in September, so a more convenient date of October 26 was chosen.

Dalton was born at Eaglesfield in Cumbria and spent his early years there. He moved to Kendal in 1781 to teach at a school run by his brother. He benefited from the informal tuition of Elihu Robinson in Eaglesfield and John Gough at Kendal. They encouraged him to develop his interests in natural history, mathematics, and natural philosophy. In 1787, encouraged by Gough, he started a detailed daily weather record, continuing without fail until the day before his death 57 years later.

At Kendal he started giving public lectures on various scientific topics, and in 1793 published his first book Meteorological Observations and Essays. That year his scientific activities resulted in his appointment as a teacher at the New College in Manchester.

Manchester is where Dalton remained, and where he did all his subsequent scientific work. He joined the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, and published many papers in its Memoirs. His first paper was on colour blindness, from which he himself suffered. It was the first scientific description of the condition, which is still sometimes known as Daltonism.

Picture: © Shutterstock

Setting a new direction for chemistry

Dalton is of course primarily remembered for his atomic theory, the first hint of which he published in 1803. Lavoisier had in 1789 given the modern definition of an element as a substance that cannot be decomposed into anything simpler.

The concept that matter might ultimately be composed of minute indivisible atoms had first been suggested in ancient Greece, but Dalton proposed that each of Lavoisier’s elements was composed of its own kind of atom, identical to others of the same element, but differing from those of other elements, especially in weight.

He produced the first table of atomic weights, but uncertainty remained about the values for many years, because of the difficulty, at the time insurmountable, of determining what we would now call molecular formulae. For quantitative work, many chemists continued to use the experimentally determined equivalent weights.

But this should not blind us to the fact that Dalton’s theory set chemistry along its modern path. Chemical reactions could now be explained by atoms combining to form aggregates. These compound atoms (as Dalton called them) had properties which differed from those of their constituent elementary atoms. Compounds might be decomposed back into their constituent elements, but the elementary atoms could not be destroyed or created by chemical means. Hence Dalton’s atomic ideas immediately suggested a theory of chemical change which we still recognise today. Furthermore, while the attempts of the alchemists to make gold by chemical means had always met with failure, their dreams now became a theoretical impossibility.

Picture: © David Leitch

An anniversary celebration

Anniversaries provide appropriate occasions to remember significant events or personalities in the history of science. A major celebration took place in Manchester in 2003 on the 200th anniversary of Dalton’s first publication on his theory, but the 250th anniversary of his birth could not be allowed to pass without also being marked.

Appropriately enough, this year’s celebrations were organised by Dr Diana Leitch, current President of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, and also a member of the RSC Historical Group. Dalton was himself President of the Lit. and Phil. for 28 years. Among the many guests present was Steve Howe who, soberly dressed in period Quaker costume, impersonated John Dalton.

The first part of the event took place in the chemistry department of Manchester University. The proceedings were opened by Professor Steve Liddle, who stressed the long association of Manchester University with atomic research. Professor David Phillips, former president of the RSC, then spoke. He described how the Royal Society of Chemistry, whose precursor the Chemical Society had been founded three years before Dalton’s death, had as part of its mission the aim of improving the public perception of chemistry and chemists. He cited recent research, which had shown that public attitudes to chemistry were more positive than anticipated.

Picture: © David Leitch

Chemical Landmarks

One of the many ways in which the RSC reached out to the public was through the Landmark scheme, and David Phillips, past president of the Royal Society of Chemistry, presented two plaques to commemorate John Dalton.

The first marked the current anniversary, and will be erected on the Ape and Apple pub in John Dalton Street. This is owned by the Manchester brewery of Joseph Holt, which commenced operations in Manchester in 1849, five years after Dalton’s death. It was accepted on behalf of the brewery by Marc Brodie, the estates manager.

Picture: © David Leitch

The second plaque had in fact been presented before, as Sir Harry Kroto had unveiled it on the occasion of the bicentenary of the atomic theory in 2003. It had been positioned in the Peace Garden in St. Peter’s Square, but it had been removed to make way for a new tram station. After its removal it had been lost, but persistent enquiries by Historical Group member Dr Gerald Hayes located it to a shed in Herefordshire, fortunately displaying only minor damage. The plaque was now presented a second time, on this occasion to the Literary and Philosophical Society, who will display it in their offices. Sadly Sir Harry Kroto died earlier in 2016, but his widow was present to see the plaque donated to its new owners.

Picture: © David Leitch

The Dalton Medal

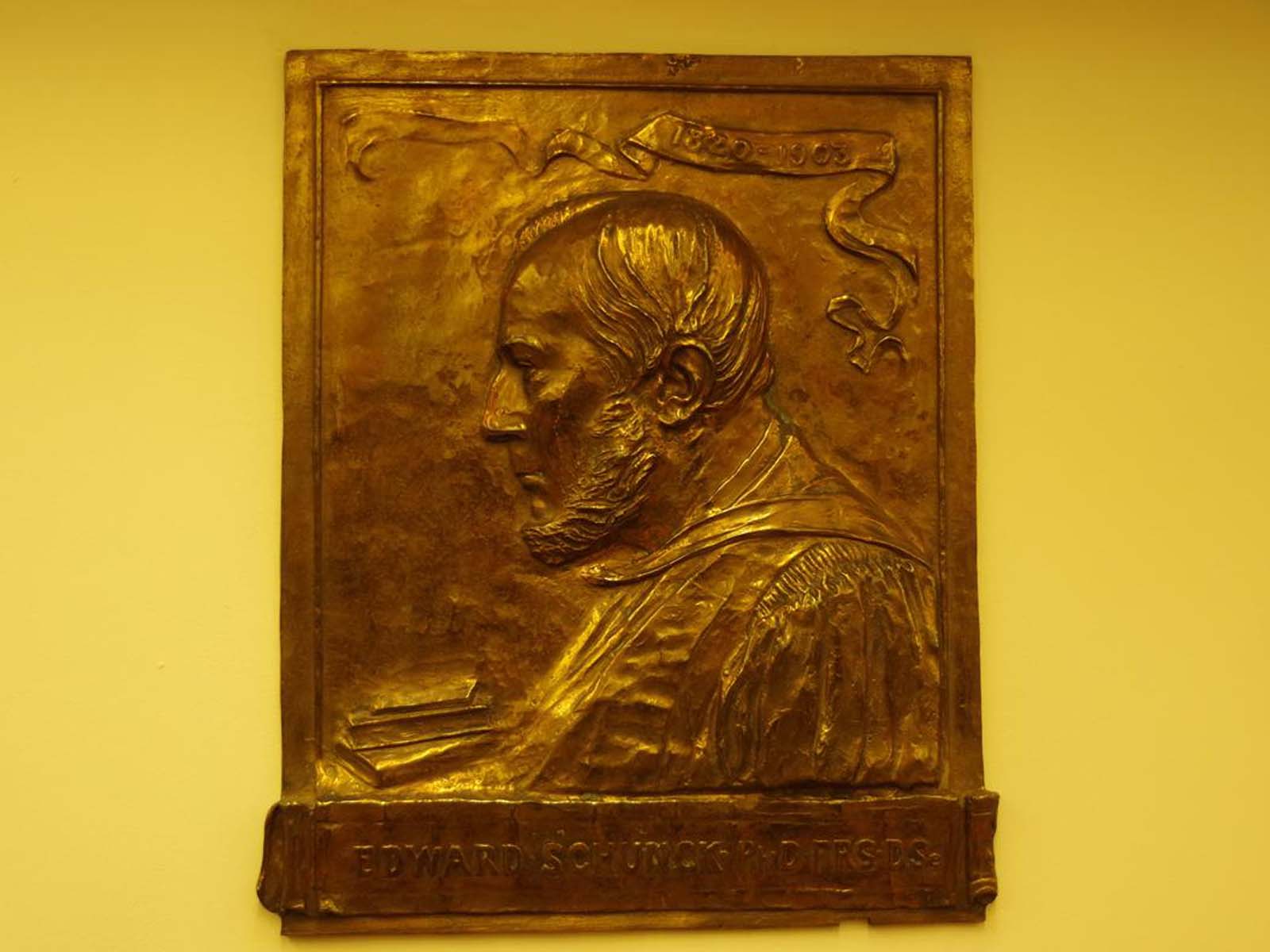

After a reception hosted by the Royal Society of Chemistry, we moved across the road to the physics department, where Diana Leitch introduced the second part of the evening. This commenced with the award of a Dalton Medal. Diana explained that a Dalton Medal has only been awarded on fourteen previous occasions, the first being presented to Edward Schucnk in 1898. All awardees have been eminent scientists with Manchester connections.

Picture: © David Leitch

Today’s recipient was Professor Sir Kostya Novoselov FRS, Langworthy Professor of Physics and joint winner of the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery of graphene. After the presentation Professor Novoselov gave a lecture entitled The history of sp2 carbon in England. Novoselov described some episodes in the history of graphite and other carbon-based materials.

He alluded to the first ever graphitic mines in Seathwaite (Lake District), the discovery of the structure of graphite by John Desmond Bernal, the very painful experience with Wigner energy in graphite during the Windscale fire, the discovery of fullerenes by Kroto, Smalley and Curl, and the first isolation of graphene. He concluded by referring to some current advances in carbon science and he discussed the possible future applications of some of these remarkable materials.

The event was a fitting tribute to the memory of John Dalton, and a reminder that today Manchester is at the forefront of research into modern materials.