The Chemical Society & the Royal College of Chemistry

Royal College of Chemistry, Oxford St, London, 1896 Picture: © Imperial College London

175 minutes for chemistry

Bill Griffith, Emeritus Professor at Imperial College London, explains how he spent his 175 minutes for chemistry reflecting on the rewarding relationship between Imperial’s first constituent college – the Royal College of Chemistry – and the Royal Society of Chemistry’s earliest precursor, the Chemical Society.

As RSC News readers will know, the Chemical Society (CS, precursor of the Royal Society of Chemistry) was founded 175 years ago. I've used my 175 minutes for chemistry to highlight the fruitful relationship between the CS and the Royal College of Chemistry (RCC), established just four years later.

In their classic account of the first 100 years of the CS, Moore and Phillip1 wrote:

…it is difficult to overestimate the significance of the Royal College of Chemistry ... in the development of the Chemical Society.

So, what was this grandly-named Royal College, and is this epigraph true? The RCC was initially a private venture. In the early 19th century it was realised that Britain needed more practical chemists, and a fund was established for an institution to teach chemistry emphasising the practical side.

There were over 700 donors including Gladstone and Disraeli; the Prince Consort took a keen interest, inviting the charismatic German chemist August Hofmann to lead it. This was a brilliant choice: Hofmann, only 27 years old, was an established chemist and inspirational teacher.

London premises were acquired at 16 Hanover Square, and laboratories built at the adjoining 299 Oxford Street, marked now by a rather dingy RSC Landmark plaque. An early, albeit disappointing, connection with the CS was that the latter, needing a better home than the Society of Arts in John Adam Street, attempted in vain to rent space in the RCC Oxford Street building.

By 1853, the RCC had become bankrupt and was taken over by the Government School of Mines, though retaining its name and location. In 1872 it moved to South Kensington and was renamed the Royal College of Science (RCS) and in 1907 it was subsumed into Imperial College as its Department of Chemistry. Thus the latter, of which I am a member, has 171 years of history.

There were 26 students in the first year (1845) of the RCC, and some of those were already CS members. Warren de la Rue – his father Thomas started the famous printing firm – was an 1841 CS founder member and twice its president (1867–9 and 1879–80); he joined the RCC in 1845.

Another 1845 RCC member (and CS Council member) was Frederick Abel, who, with Dewar, discovered cordite and won a legal case against Nobel over their priority. Hofmann was an early CS enthusiast, becoming its foreign secretary (1847–1861) and president (1861–3). In 1867, he set up its German equivalent, the Deutsche Chemische Gesellschaft, very much on the lines of the CS.

Robert Warington (prime founder of the CS and its first secretary) helped the early RCC, and his son Robert became an assistant of Edward Frankland at the college.

Other early CS and RCC members include William Crookes, later to discover thallium, and William Perkin who at age 18 discovered the dye mauveine in 1856. He made his fortune with it and, some say, founded the British chemical industry.

Hofmann, the first professor of the RCC, became internationally renowned with his work on organic nitrogen bases, organic syntheses, molecular structures and chemical models. Though Thomas Graham of University College (first president of the CS in 1841) and he were rivals, they worked together to rebut the claim by German brewers that the characteristically bitter taste of English beers was obtained by adding strychnine to them.

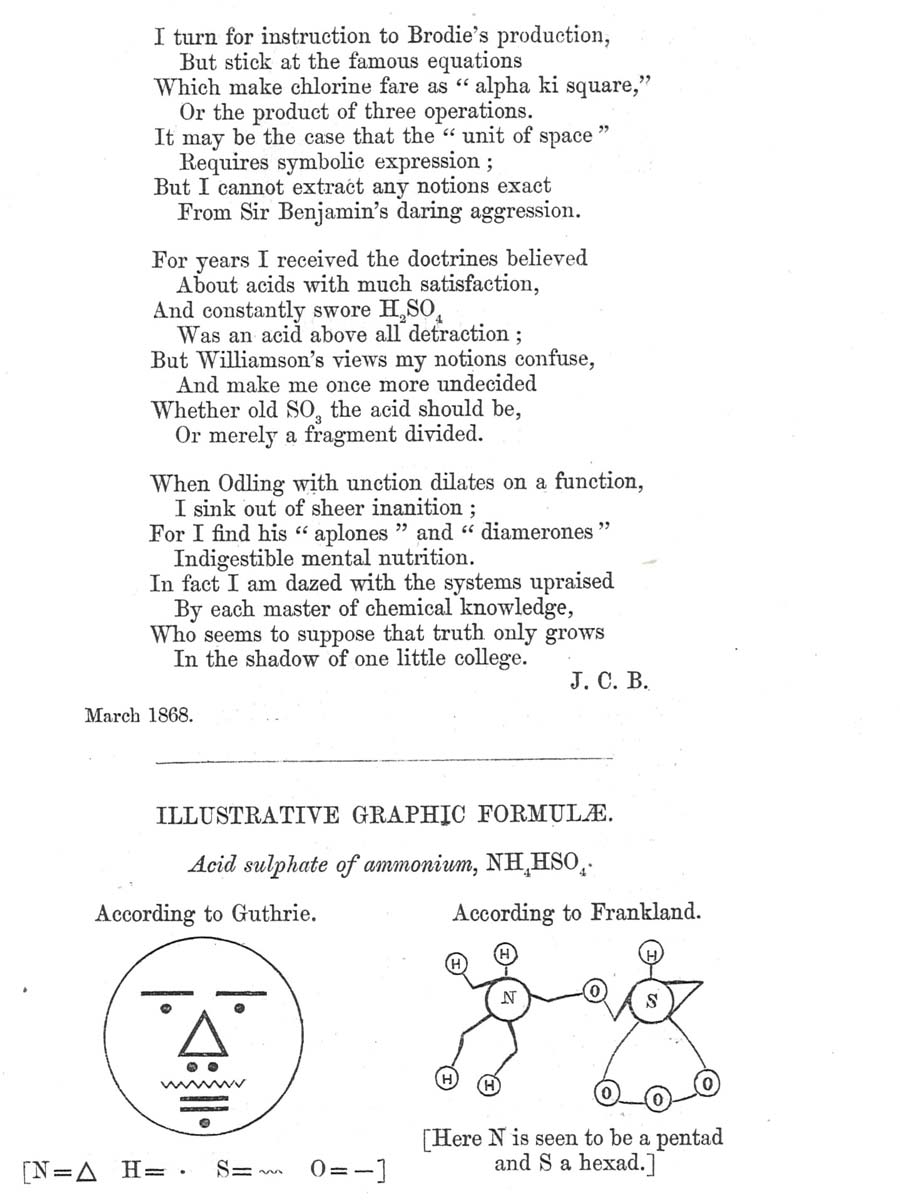

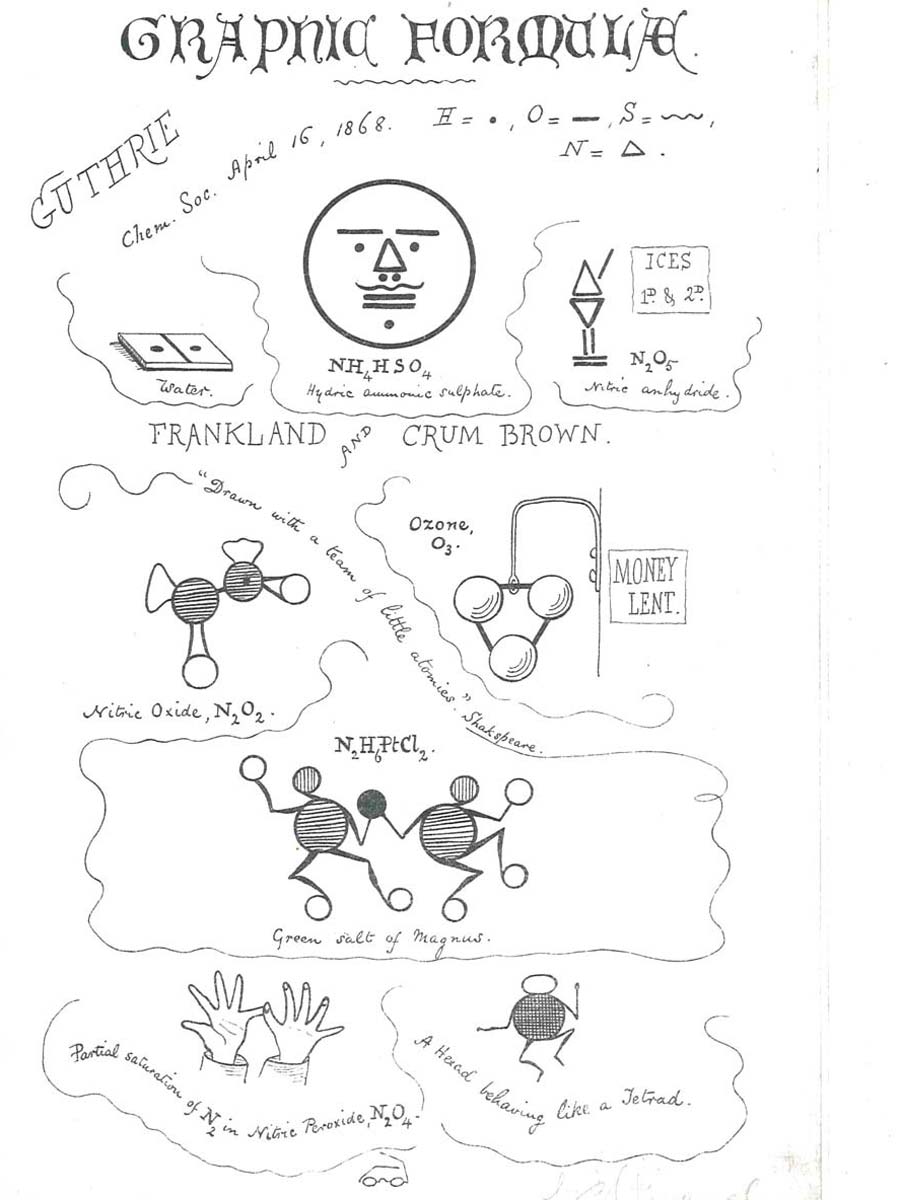

Their joint report of 1852 comprehensively disproved this; Hofmann said that his RCC staff drank much more of the free beer donated by grateful brewers than did their UC collaborators. His successor as professor at the RCC from 1865-85 was Edward Frankland. A fearless experimentalist, whose new organometallic compounds caused several fires and explosions, he coined the word 'organometallic', and was the first to use 'bond' in a chemical sense. His development of a modern theory of valency was paramount – he is often called ‘the father of organometallic chemistry and valency’. His friend John Cargill Brown published this playful depiction in a CS club journal of a Frankland structural formulation.

© Royal Society of Chemistry

© Royal Society of Chemistry

Women were not allowed to join the CS in the 19th century (a marked difference from the RCC and its successors, which from 1845 admitted women at all levels). Thomas Thorpe and William Tilden, prominent RCC members later to be CS presidents, played an active but frustrating role from 1890 in trying to introduce female CS membership – women were not admitted until 1920.

Of the 91 presidents of the CS and RSC from 1841–2016, a disproportionately high number (35), in view of the national coverage of the society, were associated with the RCC and its successors as students, staff or emeriti. The current president, Dominic Tildesley, was an Imperial College visiting professor. It seems likely that this close association will continue through to the bicentenaries of both our organisations, and no doubt beyond.

- T. S. Moore and J. C. Philip, The Chemical Society 1841–1941: a Historical Review, Chemical Society, London, 1947.

Words by Bill Griffith, Department of Chemistry, Imperial College, London.