Chemistry - A universal language

Prof. Peter J. H. Scott, PhD, MRSC, CChem is a faculty member at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA, where he is an Assistant Professor of Radiology, a Member of the Interdepartmental Program in Medicinal Chemistry and Director of the PET Center. Picture: © Peter Scott

175 minutes for chemistry

Peter Scott spent his Time4Chem writing about his experiences as an international chemist and the importance of collaboration across borders

As a youngster I was an avid Sherlockian, and was fascinated by the various chemistry experiments that Sherlock Holmes was always conducting in the stories. This, along with a couple of exceptional science teachers in middle school and high school, instilled in me a love for chemistry, medicine and forensic science. In fact, I almost studied medicine at University, but ultimately decided that I enjoyed chemistry too much to give it up! After researching University courses, the BSc in Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Chemistry offered by Loughborough University was most in line with my interests and so that is where I landed as an undergraduate.

As part of my undergraduate degree, my 3rd year was spent in industry, working for Aventis Pharma in Robert Clayborough’s group. I knew by then that I wanted a research career in chemistry and that a PhD was my next step. I was leaning towards organic chemistry and Rob agreed: “With a PhD in organic chemistry, you can do anything,” he once told me, and those words have stuck with me ever since. I joined Patrick Steel’s group at Durham University for my PhD research, where I learned a lot of organic, fluorine and organometallic chemistry and gained an appreciation of a lot of technologies which impact chemistry and vice versa (e.g. microwave chemistry, solid-phase organic synthesis).

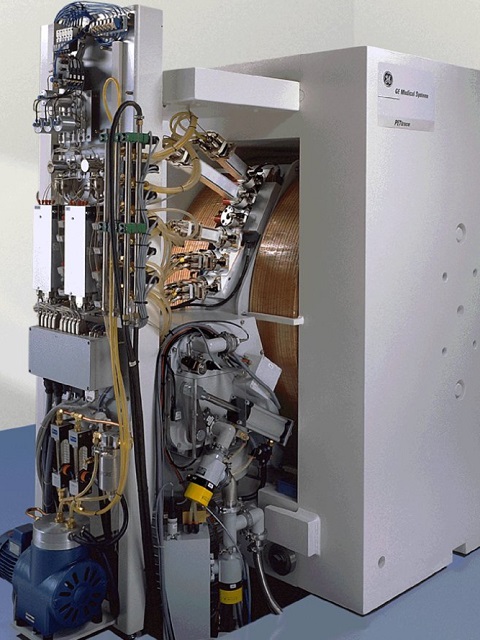

A cyclotron, used for radionuclide production Picture: © Peter Scott

"A career in chemistry really does let you see the world"

Following my PhD I decided to do post-doctoral research in the United States, initially with Huw Davies at the State University of New York at Buffalo, to expand my background in organometallic chemistry. While in Huw’s group I was preparing tropane analogs that I would send to a radiochemistry lab for radiolabeling and imaging; this was an important turning point in my career, as it was my introduction to the fascinating world of molecular imaging. I chose to do a second post-doc with Michael Kilbourn at the University of Michigan to explore the field further and get formal training in radiochemistry and positron emission tomography (PET) imaging. When I walked into the multi-million dollar PET Center at the University of Michigan Medical School for the first time, complete with cyclotron for production of PET radionuclides, gleaming stainless steel hot-cells (lead-lined fume hoods) and state-of-the-art automated synthesis modules for cGMP compliant radiopharmaceutical synthesis, and PET scanners (for rodents, monkeys and humans), I caught the molecular imaging bug and chose it as the focus of my independent research career. Ultimately, organic/medicinal chemistry and radiochemistry underlie all that we do, and in a way that I see the positive impact that it has on patients’ lives and pharma R & D programs on a daily basis. Ten years in and working in diagnostic radiology, at the interface between chemistry, physics, biology and medicine, still fascinates and challenges me. Moreover, whether it’s visiting collaborators in other countries or attending scientific conferences in, for example, Europe, Asia or America, I consider myself very lucky that a career in chemistry really does let you see the world.

The PET centre at the University of Michigan Picture: © Peter Scott

From Loughborough to Michigan

I run the PET Center at the University of Michigan, which presents the interesting challenge of running a traditional academic group and an FDA-regulated drug manufacturing facility in the same space! My academic group is a busy lab composed of undergraduates, PhD students and post-docs conducting research in two main areas: late-stage fluorination (with the PET radionuclide fluorine-18 that has a very short half-life of 109.77 min) and radiopharmaceutical discovery. The former is focused on development of green radiochemistry (Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 14805) and, through an exciting collaboration with Prof. Melanie Sanford at Michigan, development of methods for rapidly synthesizing challenging radiopharmaceuticals used novel copper-mediated fluorination reactions (for an overview see: Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 4545). The latter concentrates on design, synthesis and evaluation (in rodents and monkeys or using post-mortem human tissue) of new radiopharmaceuticals for functional neuroimaging in dementia with the aim of using PET imaging to understand, for example, the Alzheimer’s disease cascade. The drug manufacturing arm of my group is composed of technical staff who prepare radiopharmaceuticals for daily clinical use within the University of Michigan Hospital and for PET imaging studies with collaborators in the (bio)pharmaceutical industry. My favourite aspect of running such a multidisciplinary group is that 10 minutes after we have prepared a radiopharmaceutical it is being injected into a rodent, monkey or human. Then, a few hours later when data processing has been completed, I have a PET scan to evaluate and determine how our molecule behaved. Did it, for example, cross the blood-brain barrier or get taken up in a tumour as expected, did it have suitable pharmacokinetics for imaging and/or therapy, where else in the body did it go, or how was it excreted? Having this translational mechanism available allows us to develop a molecule from scratch and take it all the way to clinical trials ourselves, and with our physician and industrial collaborators we can use PET imaging to advance personalized medicine (e.g. early diagnosis of disease and establishment of therapy on a patient-by-patient basis) and drug discovery (e.g. confirm target engagement by a new drug candidate).

Peter's group at the University of Michigan Picture: © Peter Scott

Collaboration across borders

One of the fascinating things I find about chemistry is that nomenclature gives chemists a universal language that transcends traditional language barriers or international borders. Reflecting this, we have collaborations with colleagues in the United States as well as Canada, Mexico, Japan, China, the UK and throughout Europe that allow us to operate in the global radiochemistry landscape. The chemistry community has always had a global feel to it, sharing ideas through the literature and international meetings, but I think it is even more important in the PET radiochemistry community. The short shelf-life of our radiopharmaceuticals (often ≤6 hours) means if, for example, multi-center animal studies or clinical trials are to take place, a global network of radiochemistry labs is required in close proximity to PET imaging sites as the drugs cannot be manufactured and shipped from a centralized location. This requires careful coordination by radiochemists with an appreciation of the local regulations governing drug manufacture, radiation safety, animal use and/or clinical trials in each country, and is critical if the benefits of molecular imaging are to be made available to patients worldwide.

Picture: © University of Michigan

Studying abroad

My advice to students thinking of studying abroad is to compete an undergraduate degree in the UK, because I think the classical chemistry training you get through an RSC accredited degree in the UK is one of the best in the world, and it will serve you well throughout your career. Subsequently, completing a PhD or a post-doctoral fellowship outside of the UK is a great opportunity. Not only is it a chance to travel and see some of the world when you are young and have less ties, but also the experience of moving to another country takes you firmly out of your comfort zone and presents many opportunities for personal and career growth. Whether or not you return to the UK afterwards, you will be worldlier, have expanded international social and professional networks, and boast the much-coveted “international experience” that employers are increasingly looking for in new hires.