Chemists in the First World War

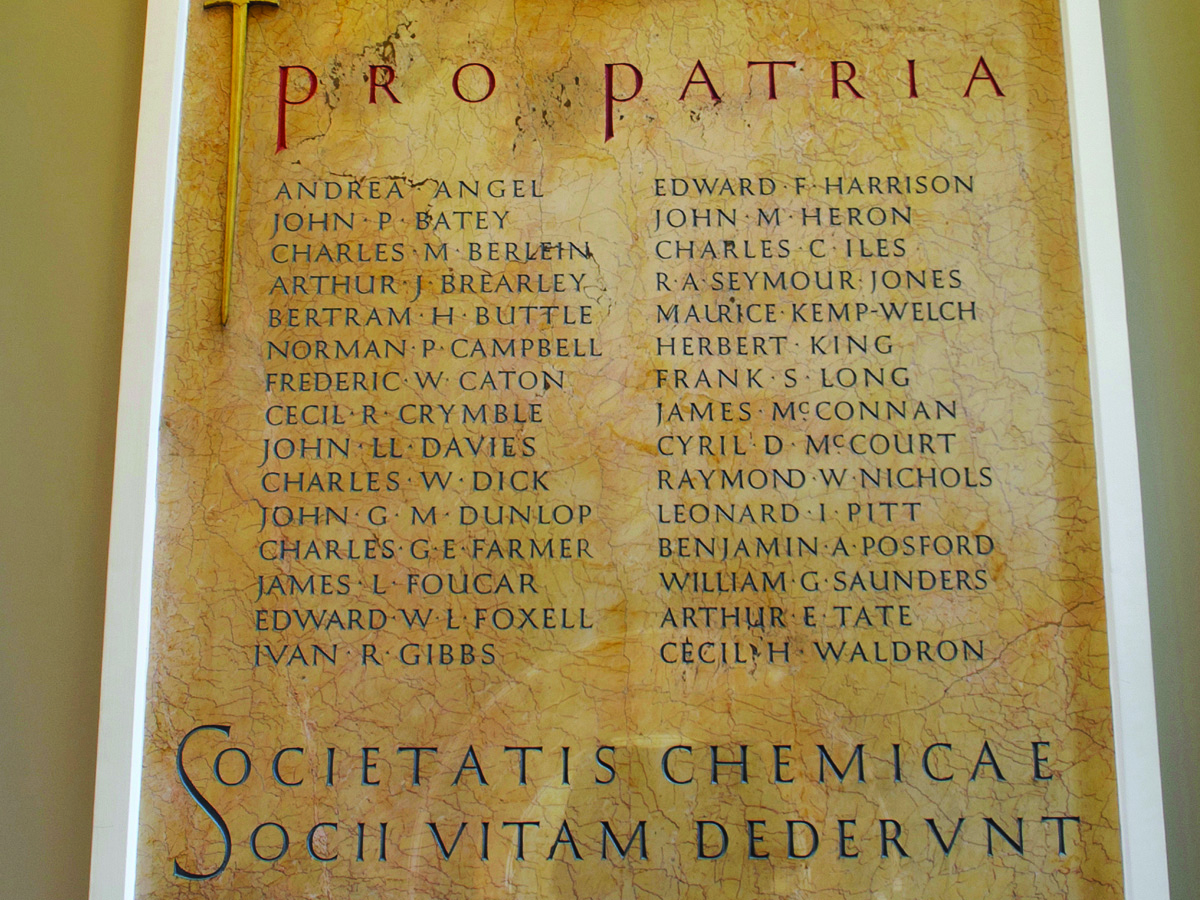

The memorial at Burlington House. Picture: © Royal Society of Chemistry

David Allen, Royal Society of Chemistry

The consequences of Britain’s declaration of war by King George V’s government in Whitehall in August 1914 would eventually reach

right across the globe. At the same time, the knowledge gained by the chemical science community and the bravery of its individuals, represented by the Chemical Society – less than a mile from Whitehall in Piccadilly – were soon to become assets in ways that no one had previously imagined.

The First World War was the first conflict in which chemistry was used for both offensive and defensive strategies. With Germany leading the way in the chemical sciences, it was imperative for the Allies to catch up on knowledge quickly. One key resource that the British chemical community had at their disposal was the library of our precursor, the Chemical Society, at Burlington House. In its collections, it held many German journals and books on applied chemistry that were unavailable elsewhere. So from the summer of 1915 to the summer of 1919, the library did not close for a single working day and was in frequent use by people working for the War Office and other government departments.

Controversy surrounding members

While the Chemical Society’s library was being used to support the war effort, an internal dilemma threatened to undermine public opinion of the society. The question of whether to remove the names of the Honorary German Fellows, regarded to be ‘alien enemies’, was discussed in three separate Council meetings. Each time, Council decided to defer any action until after the war, when they would know more about the activities of the scientists in question. In June 1915, “by a large majority [Council] decided that no steps can, consistently with the dignity of the Society and with due regard to British ideas of justice, be taken in the above direction until after the cessation of hostilities.”

Despite this decision, the issue piqued the interest of the national press, and the failure of the Chemical Society to expel its German members was heavily criticised. While the controversy appeared to be about a British learned society seeming to support the enemy, in reality, the issue concerned less than a dozen well-respected chemists who were close to retiring or had already done so.

Following increasing pressure, Council resolved to put the decision into the hands of its Fellows and, in June 1916, asked them to vote. The result, by a small majority, was in favour of the removal from the registers of Adolf von Baeyer, Theodor Curtius, Emil Fischer, Carl Graebe, Paul Heinrich von Groth, Walther Nernst, Wilhelm Ostwald, Otto Wallach and Richard Wilstatter. Eugen Bamberger had already resigned. By 1929, four of these men – those who had not since died – were re-elected.

Remembering those who served

When the war ended, many communities came together to ensure that future generations would not forget. Both the Chemical Society and the Institute of Chemistry commissioned memorials to their Fellows who had died on active duty. When, decades later, these societies merged to become the Royal Society of Chemistry, both memorials moved to Burlington House. Together, they commemorate 82 men, however, intriguingly and inexplicably, one Fellow’s name was not included.

John Griffiths: the forgotten man

His name is John Griffiths. Born in August 1881, he received his education at the University of North Wales. After leaving university, he taught science at a college in Shropshire before moving to Larne Grammar School in County Antrim. There, he captained the newly created Larne Rugby Football Club and led the team to victory. At the outbreak of war, he took a commission with the Ulster Volunteers and crossed to France in 1915 with the Royal Irish Rifles. In June 1916, he was wounded in a bombing raid and was killed less than a month later, while leading his men up the enemy’s trench at Beaumont-Hamel. Captain John Griffiths was mentioned in Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig’s dispatches of 13 November 1916 for distinguished service in the field, he was one of 19,000 to die during the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

Eric Rideal: From gas respirators to becoming our president

Besides the Fellows that died on duty, many other men and women contributed to the war effort and survived. One such man was Eric Rideal. Son of renowned chemist Samuel Rideal, Eric studied chemistry in Germany and gained his PhD in 1912.

When war began, he was fixing water supplies in Ecuador but immediately returned to the UK to enlist. He initially worked with Edward Harrison in London to develop gas respirators, and later went to the Somme with the Royal Engineers to supervise the supply of water to the troops. He was invalided at the Battle of Carboy Wood and sent home in 1916, where he researched catalysis at University College London for the Munitions Inventions Department. In 1918, he was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for his work during the war.

Following the war, he went to the University of Illinois as a visiting professor and returned home a year later to take up a lectureship in physical chemistry at Cambridge, where he became professor of colloid science in 1930. During this time, he founded the Colloid Science Laboratory, which was later used for work during the Second World War – a contribution for which he was knighted

in 1951.

In addition, Eric became president of the Faraday Society (1938-1945) and of the Chemical Society (1950-1952). Today, the Rideal Trust, which is jointly administered by us and the Society of Chemical Industry, provides travel bursaries to promising academic research workers in the general field of colloid and surface science.

100 years later

To commemorate the men named on the two memorials and to remember the contributions made by those men and women who survived the war, we have produced a special booklet, Pro Patria.

In addition, the RSC Historical Group has organised a meeting about chemistry and the Great War for 22 October. Featuring leading international experts, the event will take place at Burlington House and will be live-streamed at the Catalyst Centre in Widnes. If you would like to attend the event, visit for more information.

We will also be publishing a collection of essays that examine various facets of the role of chemistry in the First World War to mark the centenary. The book by Michael Freemantle, called The Chemists’ War, will be of interest to both scientists and historians and will available from November.