A time for action

Dr Patricia Fara, science historian at the University of Cambridge, uncovers the story of women’s hidden battle on the home front.

AUTHOR: Patricia Fara

"Have you ever tried to run and jump in petticoats?" exclaimed a biologist. "Well, think what it must be to live in them – soul and mind and body!"

Both literally and metaphorically, in the early twentieth century female scientists were trapped within their bodies and their clothes. They encountered prejudice wherever they turned.

Why, wondered an Edinburgh student, did traditional male chivalry vanish as soon as she and her friends walked into a classroom? “The tapers and tadpoles of the back benches begin to howl and screech with all the lustiness of rural louts,” she remarked bitterly, “and seem to be as much amused as if they saw a picked company of the far-famed Dahomeyan Amazons march in all the glory of their military attires.”

Women-only chemistry laboratory at Newnham College Cambridge Picture: © Newnham College Cambridge

For a woman to get a degree in science demanded not only intelligence, but also resilience and determination. When the First World War started, many female scientists seized the opportunity to prove that they could carry out work usually reserved for men.

<!-- .pull-neighbour { float: right; width: 30%; min-width: 190px; overflow-wrap: break-word; font-weight: 700; font-family: MuseoSlab700Regular, museo_slab500, museo_sans_500regular, Arial; font-style: strong; color: #6b6b6b; padding: 16px 32px !important; margin-top: 16px; -webkit-margin-before: 0; -webkit-margin-after: 0; -webkit-margin-start: 0px; -webkit-margin-end: 0px; -ms-hyphens: auto; -moz-hyphens: auto; -webkit-hyphens: auto; hyphens: auto; text-align: left; letter-spacing: -0.03em; font-size: 20px; line-height: 26px; quotes: "\201C""\201D""\2018""\2019"; letter-spacing: -0.00em;} .footer { padding-top: 16px !important; font-family: MuseoSlab700Regular, museo_slab500, museo_sans_500regular, Arial; font-style: normal; color: #989898; font-size: 12px; line-height: 16px; } -->Margaret Turner, a chemist responsible for preparing large-scale supplies of essential drugs at the University of Aberystwyth, wrote a heartfelt letter to the Royal Society’s War Committee: "I was one of the workers in the preparation of diethylamine some weeks ago and should be glad to hear of any further help I could give. I can put all my time and energy at your service for the next six weeks, and am anxious to know whether the few helpers down here, could not be allowed to contribute further to the needs of the country?... I, for one, am willing and eager to give up all ideas of holiday while there remains so much to be done."

The new red-brick universities were keen to demonstrate their national significance as well as their high academic standards, and they immediately switched their research programmes to match military requirements. For example, at Birmingham the chemistry department collaborated with Lever Brothers and the Ministry of Munitions to develop military products, such as toxic gases that could penetrate the filters in German masks. Because so many male scientists were being sent overseas, female academics flooded in to compensate for the shortage. When there was only one man left in the chemistry department at Sheffield, women took over to teach, synthesise large quantities of local anaesthetic, and carry out metallurgical processes.

Women working in a munitions factory during WWI Picture: © US Army/Science Photo Library

Imperial College London was especially heavily involved in wartime activities. Several buildings were appropriated by the Army as offices for clerical workers or as accommodation for recent recruits. Twenty women worked in the Royal Flying Corps drawing office, and space also had to be found for the volunteers in the Women’s Emergency Corps. For the first time, professional female scientists were allowed to emerge from their laboratories and lecture in front of mixed audiences. Two women were promoted to supervise the fly room for developing insecticides, and when a male student accidentally gassed himself with phosgene, it was a woman who rescued him (they later married).

Martha Annie Whiteley was in charge of an eight-woman team testing explosives at Imperial College London during the War Picture: © Imperial College London Archives

The grounds started to resemble a military encampment, equipped with experimental trenches dug in the gardens, where an eight-woman team tested explosives and poisonous gases. The chemist in charge was Martha Whiteley, who had previously been working at Imperial on synthetic barbiturates. Like all female scientists, she had established her career in the face of mockery and prejudice. But she was also exceptional in not coming from a wealthy family. Her father was a surveyor who could not afford to buy an expensive education – especially for a girl – and she was forced to compete for the minuscule number of available scholarships.

Girls’ schools rarely taught science, but Whiteley went to one of the high-powered London high schools financed by the Girls’ Public Day School Company. In 1887, she moved on to study science at Royal Holloway, then a residential women’s college associated with the University of Oxford. She was in the first intake of 28 students, her fees of £90 more or less covered by prizes and scholarships. The chemistry laboratories had not yet opened, so the four science students used three rooms equipped with sinks and taps, "and did Chemistry, Physics or Botany according to the way the wind blew, because one chimney always smoked". The daily regimen was strict: a wake-up bell at 7 am, a compulsory service at 7:55, and breakfast at 8:20 before lectures from 9:00 to 1:00. The early afternoon was given over to tennis and other games, followed by tea, private study, dinner and evening prayers.

Whiteley graduated with a University of London degree when she was 24, but lacking either rich parents or a husband to support her, she spent the next eleven years teaching. In her spare time she carried out chemical research, for which she gained her DSc in 1902.

<!-- .pull-neighbour1 { float: left; width: 30%; min-width: 190px; overflow-wrap: break-word; font-weight: 700; font-family: MuseoSlab700Regular, museo_slab500, museo_sans_500regular, Arial; font-style: strong; color: #6b6b6b; padding: 16px 32px !important; margin-top: 16px; -webkit-margin-before: 0; -webkit-margin-after: 0; -webkit-margin-start: 0px; -webkit-margin-end: 0px; -ms-hyphens: auto; -moz-hyphens: auto; -webkit-hyphens: auto; hyphens: auto; text-align: left; letter-spacing: -0.03em; font-size: 20px; line-height: 26px; quotes: "\201C""\201D""\2018""\2019"; letter-spacing: -0.00em;} .footer { padding-top: 16px !important; font-family: MuseoSlab700Regular, museo_slab500, museo_sans_500regular, Arial; font-style: normal; color: #989898; font-size: 12px; line-height: 16px; } -->The following year, she joined the staff at one of the three colleges that soon merged to form Imperial College. After several internal promotions, she eventually became the equivalent of a modern Reader until she retired in 1934; she was made an Honorary Fellow in 1945.

An experienced school teacher, Whiteley transferred her experiences to university classes, and clearly excelled. One student recalled that just after the War, she “was in charge of the undergraduates’ organic laboratory…They were nearly all men and a very lively lot – being mainly ex-Service men, but she had them completely under control. She managed to turn them into fairly tidy, efficient practical workers.” In collaboration with her former supervisor, Jocelyn Thorpe, to whom she paid great tribute for his support, she wrote a four-volume encyclopaedia of organic chemistry. Based on her long experience of running the advanced course, it became a standard classic and over the years was produced in several editions.

Whiteley’s distinguished career was unique for a female chemist in this period. Several women found places as assistants to men, and a few became renowned for their research in a non-traditional field. For a woman to stake out her own patch in unexplored territory was the quickest, if not the surest, way to an outstanding reputation. To take the most obvious example, Marie Skłodowska Curie was one of the first scientists who investigated the new phenomenon of radioactivity. Constantly worried about her claim to ownership in her adopted country of France, where as a wife she was legally a non-person, Curie repeatedly and systematically buttressed her assertions of priority. But Whiteley was different: she chose a well-established topic (amides and oximes), set up her own research programme with both male and female students, and worked for many years at Imperial College, a major educational institution.

<!-- .pull-neighbour { float: right; width: 30%; min-width: 190px; overflow-wrap: break-word; font-weight: 700; font-family: MuseoSlab700Regular, museo_slab500, museo_sans_500regular, Arial; font-style: strong; color: #6b6b6b; padding: 16px 32px !important; margin-top: 16px; -webkit-margin-before: 0; -webkit-margin-after: 0; -webkit-margin-start: 0px; -webkit-margin-end: 0px; -ms-hyphens: auto; -moz-hyphens: auto; -webkit-hyphens: auto; hyphens: auto; text-align: left; letter-spacing: -0.03em; font-size: 20px; line-height: 26px; quotes: "\201C""\201D""\2018""\2019"; letter-spacing: -0.00em;} .footer { padding-top: 16px !important; font-family: MuseoSlab700Regular, museo_slab500, museo_sans_500regular, Arial; font-style: normal; color: #989898; font-size: 12px; line-height: 16px; } -->During the War, Whiteley headed a team of seven women. Putting to one side her research into drugs, she shifted to examining gases. And there was only one way for her group to do that effectively: by testing the gases on themselves. Although they did not share the fate of other wartime chemists who died through such self-experimentation, they went through some unpleasant experiences. Over 30 years later, in a lecture designed to inspire female students, Whiteley described how she had examined the first sample of mustard gas to be brought back to London: "I naturally tested this property by applying a tiny smear to my arm and for nearly three months suffered great discomfort from the widespread open wound it caused in the bend of the elbow, and of which I still carry the scar."

Whiteley received several tributes for her wartime research, although detailed information is hard to find because it was classified as secret. She must have felt gratified to have an explosive named after her – DW for Dr Whiteley – and also enormously proud to be awarded an OBE. But perhaps – and this can only be conjecture – she was especially pleased by a newspaper headline celebrating her as "the woman who makes the Germans weep", because of her research into tear gas.

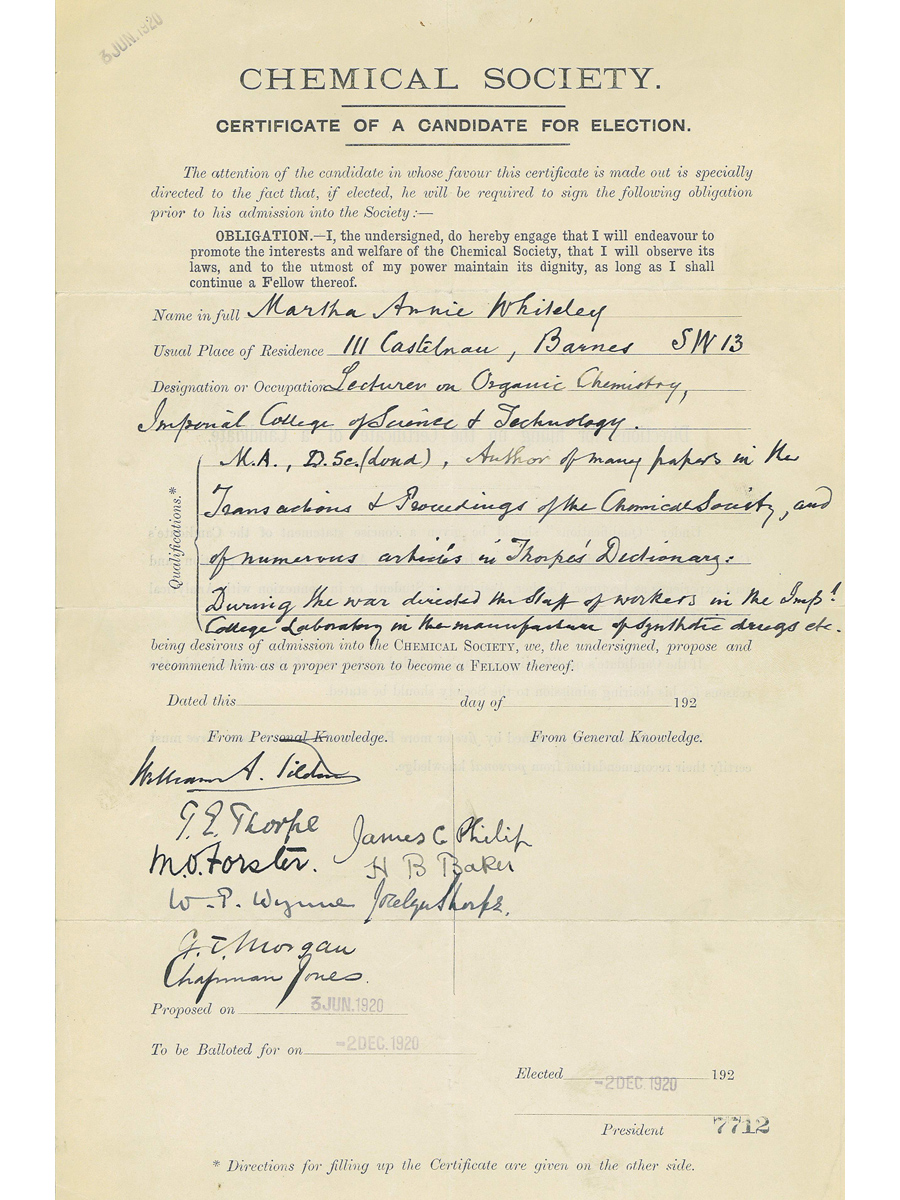

By the end of the War, female chemists were running their own research projects, lecturing at universities, writing textbooks, advising industry, inspecting factories – but they were not allowed to join the Chemical Society until 1920, following forty years of petitions, debates and manoeuvring behind the scenes. The details of who did what when can become very complicated, but this clash between two gendered scientific communities illustrates how women created their own networks and gained strength from their fellow activists. It also, less creditably, shows how much influence a few powerful men could exert.

The Chemical Society was forced to look again at their men-only policies when Marie Curie was recommended for fellowship Picture: © Science Source/Science Photo Library

The Chemical Society was founded in 1841, but it was not until 1880 that a couple of members suggested amending the constitution to allow women to enter. On three separate occasions, that proposal was shelved, but in 1904, Marie Skłodowska Curie was recommended for fellowship. What an awkward situation!

Yet again, legal advice was taken, and the final decision was an inspired compromise of the type all too familiar to anyone who has sat on committees: although as a married woman Curie was banned from being admitted normally, she could be a Foreign Fellow, a position that carried no duties or responsibilities.

At this stage, Whiteley and her colleagues decided it was time for action. She teamed up with Ida Smedley, Manchester’s first female chemistry lecturer, who founded the British Federation of University Women (BFUW). Gathering together seventeen of their female chemical colleagues, they sent in a petition pointing out that during the previous 30 years, around 150 women had been named as authors in the Chemical Society’s own publications.

Martha Whiteley's certificate of admission to the Chemical Society Picture: © Royal Society of Chemistry

But although the Council unanimously adopted their proposal to admit women, only 45 out of over 2700 members bothered to attend the special meeting called to confirm the decision – and the vote amongst them was 23 against, 22 for.

Opposition was spearheaded by the Society’s former President, Henry Armstrong, who maintained that the prime duty of female chemists was to pass on their genius to the next generation by producing baby chemists. Young women should, he insisted, "be withdrawn from the temptation to become absorbed in the work, for fear of sacrificing their womanhood; they are those who should be regarded as chosen people, as destined to be the mothers of future chemists of ability."

In 1909, someone – perhaps Armstrong – circulated a letter accusing the women agitating for membership of being linked to the suffrage movement. Whiteley, Smedley and 29 other female chemists contacted each other to compose a collective retort: they were, they wrote indignantly, united not politically, but by their love of chemistry.

The arguments and the votes rumbled on, but nothing changed until 1919, when the removal of the Sex Disqualification Act forced professional organisations to rethink their standard policy of discriminating on grounds of gender or marital status. Although many universities and other employers found ingenious ways round the problem, the Chemical Society did, at last, accept unanimously the proposal to admit female members.

Between them, around 70 men nominated 21 female candidates, who were elected as fellows of the Chemical Society in 1920, including Martha Whiteley and her ally Ida Smedley. Within a few years, she was on the Chemical Society Council, well-placed to countermand the arguments of Armstrong and his allies. But Armstrong-equivalents lived on. In 1943, when Lawrence Bragg canvassed opinions about Kathleen Lonsdale, who two years later became one of the first female FRSs, one distinguished X-ray crystallographer replied: "I must confess that I am one of those people that still maintain that there is a creative spark in the male that is absent from women, even though the latter do so often much marvellously conscientious and thorough work after the spark has been struck."