Elements in danger

Picture: © David Cole-Hamilton

David Cole-Hamilton – previously president of EuChemS – explains why we need to be mindful of many of the elements as a limited resource.

The periodic table allows us to understand chemistry at a glance, and you can tell so much about the chemistry of an element just by its position. For example, if you picked up a block of magnesium and all you knew was its atomic weight and atomic number, it wouldn’t tell you anything else. But when you see it in the periodic table you know that it can form a stable 2+ ion, that it will form a hydroxide that’s not very basic, that it won’t be very soluble in water, and that it can catch fire easily.

The trends and patterns can give you so much information. For example, silicon, in group 14, is a semiconductor. If you put a group 13 and a group 15 metal together – for example gallium arsenide – that’s a semiconductor as well. It’s astonishing that you can deduce all that just by looking at the position of an element in the periodic table.

The periodic table is so key that in my capacity as president of EuChemS I decided to try and put a periodic table in every school in Europe – to celebrate the International Year of the Periodic Table in 2019. I wanted it to be a striking image, and different from what people are used to, because making people stop and say "what’s that?!" is the way to get them interested.

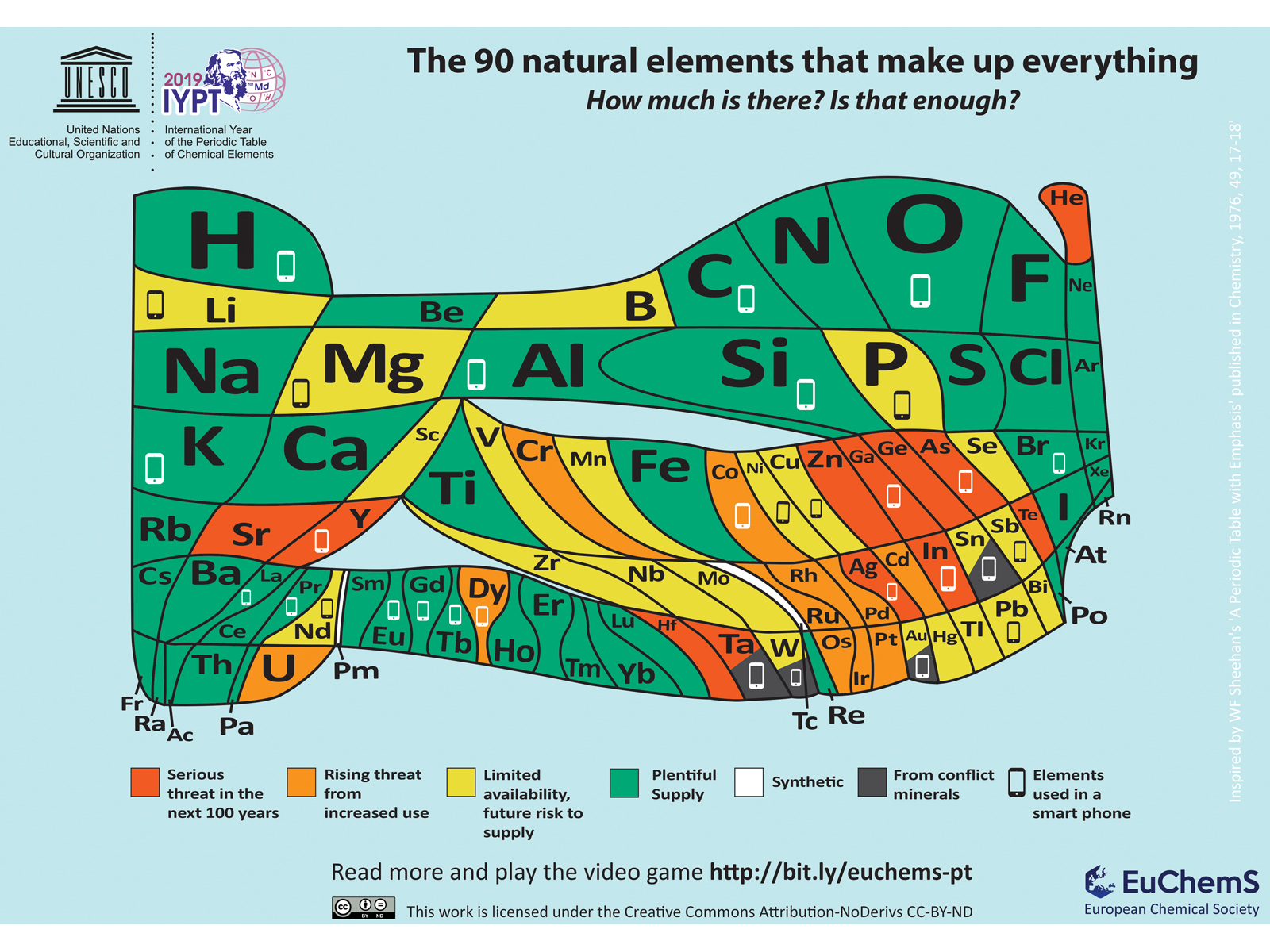

An Italian chemist called Nicola Armaroli, who is very interested in the scarcity of elements, showed me the overall shape of this version of the periodic table – which was originally designed in 1973 by W. F. Sheehan in America. We took that basic shape but had to change all the areas to reflect abundance (on a logarithmic scale) more accurately and coloured in the elements to illustrate which ones are likely to be difficult to get hold of in the near future.

Next – as an example of how much we need these elements in our daily lives – we added a phone symbol to indicate which of the elements are present in our mobile phones. We also indicate which ones are conflict minerals – that is they can come from places where people are fighting over the ownership of the mines.

I think this sends a very powerful message. On our table we’ve indicated 31 elements that are used in mobile phones. All of the conflict minerals are used in mobile phones, and some of the elements on the list have less than 100 years to go if we carry on using them at the rate that we do.

We have to question whether it’s really necessary to change over mobile phones every year or so. 10 million phones a month are changed in Europe alone. Most of them are sent to the developing world – either for reuse or for recycling – but the recycling is not efficient.

One example of an element in danger is helium. It’s used in magnetic resonance imaging and in deep sea diving, and in both of these applications the helium is recycled. But if you have a helium balloon at a birthday party, it will either deflate or burst, and either way the helium is released into the atmosphere. Helium is so light that once it’s in the atmosphere it can actually escape from the earth completely and go into outer space where it’s lost to us forever.

The second scarce element I’d like to mention is indium. Indium tin oxide is the main conducting oxide that we have, which means that indium is used in every screen that you look at. At the rate we’re using it our reserves will only last around 50 years. This means we either need to get better at recycling indium from screens, or we need to do a lot more research to identify compounds based on earth-abundant elements – those coloured green on the periodic table – that can do the same job.

We’re launching our version of the table at the European Parliament in January 2019, but we’ve already made great progress in getting it into schools across Europe. In the Netherlands the table has been handed out to 200 teachers, and in Italy they are sending a copy to every school. The Royal Society of Chemistry is going to send a copy to every one of its 50,000 members.

We’ve tried hard to make our periodic table accessible to everyone – for example we’ve made sure the colours can be identified by colour blind people, and the symbols are in a font that’s easier to read for people with dyslexia.

It’s amazing to think that everything that we see around us in the natural world is made up from just 90 building blocks – the 90 naturally occurring elements. Furthermore, these 90 elements, in different combinations, make up all of the wonders of nature, and all the technology and gadgets we use every day. We need to have a better way of dealing with these resources, or we won’t have them anymore.